The New Brunswick Election of 1866: The Colonial Vote that Unlocked Confederation

In the spring of 1866, New Brunswick became the hinge on which British North America creaked and, at last, began to swing. Confederation was still a proposal—ink on conference paper, a cabinet idea in Quebec City, a set of “Resolutions” carried by men who spoke of destiny while voters spoke of taxes, trade, and whether their own town would be swallowed by somebody else’s map. The colony had already rejected the scheme once, and loudly. That is what made the election of May–June 1866 so pivotal: it was not a first referendum-like encounter with Confederation, but a second battle fought in a harsher climate—after political maneuver, after imperial pressure, and under the gathering shadow of American danger. It was a colonial election that became, in practice, a national turning point.

Setting the Stage: Why New Brunswick Mattered

New Brunswick’s geography made it the doorway and the doormat. It sat between Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada, between the Atlantic and an interior that wanted rail lines, markets, and a defensible frontier. The grand Confederation vision required a chain that could not have a missing link; without New Brunswick, the “intercolonial” dream was a broken bridge. Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon—young, ambitious, and, by temperament, more comfortable commanding than accommodating—understood that the colony’s choice would either harden into permanent separation or become the corridor through which union could march. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography notes that Gordon pressed hard on the intercolonial railway question and worked relentlessly toward some form of union, because the rail link was “crucial” to larger unification schemes.

The vote of 1866 did not arrive out of nowhere. It arrived like the second clap of thunder after the first has already rattled the windows.

Background: The 1865 Rejection and the Anti-Confederate Moment

The immediate prelude was the election of early 1865—New Brunswick’s great anti-Confederation uprising at the polls. Premier Samuel Leonard Tilley’s pro-Confederation ministry was beaten, and an anti-Confederate government took office under Albert James Smith (with Robert Duncan Wilmot prominent), drawing energy from local suspicion: suspicion of Canadian politicians, suspicion of tariffs, suspicion that Saint John’s interests would be bartered away, and suspicion—always potent in port towns—of who would win and who would pay. Gordon later would be accused of meddling, but the deeper problem was that the anti-Confederate coalition was broad and therefore brittle: it contained men opposed to Confederation for opposite reasons—some because the plan centralized too much, others because it did not centralize enough. That internal division mattered when the pressure began to rise.

Timothy Warren Anglin, the fierce Irish Catholic editor-politician, gave voice to a key anti-Confederation argument: that the Quebec plan was being pushed through legislatures as a kind of elite seizure. He called it “a conspiracy to defraud and cheat the people out of the right to determine for themselves.” This was not mere rhetoric; it was a colonial anxiety that the machinery of responsible government could be bent by governors, councils, and conferences into something that looked constitutional but felt coercive.

Main Issues in 1866: Security, Loyalty, Religion, and the Price of Union

By 1866 the central issues had sharpened into a dangerous set of pairings:

Security vs. vulnerability. Fenian threats—Irish-American militants using the United States as a base—were not just rumor; they became political weather. The DCB biography of Anglin notes how the “loyalty issue” became decisive, aided by what it bluntly calls a “comic-opera Fenian raid on New Brunswick in April 1866.” Gordon’s own biography describes militia reforms that would matter in discouraging such raids.

Loyalty vs. disloyalty as a campaign weapon. Confederates learned to frame the anti-Confederates not simply as wrong, but as unsafe—soft on annexation, soft on Fenianism, soft on republican America. Anglin’s biography captures how Confederates tried to paint politics as a moral sorting: “loyal, Protestant, confederates versus…Catholics led by Anglin.”

Catholic voting power and sectarian heat. In 1865 many pro-Confederates had performed poorly in districts with substantial Catholic populations; by 1866, the alignment began to change. In Phillip Buckner’s scholarly account, the Irish Catholic vote “swung decisively into the Confederation camp,” unseating prominent anti-Confederates like Anglin and Costigan, while Acadian voting remained more steadily anti-Confederate in certain counties. The election was also fought with words that cut like blades: the “Anglin–Rogers controversy” turned bishop’s letters and newspaper columns into political artillery. Bishop James Rogers publicly defended Confederation and insisted his position matched “the highest and most enlightened ecclesiastics” in British North America.

Economic fears: tariffs, Saint John, and who benefits. Anglin warned that union would not deliver “wonderful economic advantages” to ordinary New Brunswickers; he believed central Canadian interests would be the main beneficiaries. Underneath this lay the hard mathematics of trade: what happens to a port economy if a new tariff wall and a new political gravity pulls commerce upriver?

Main People: The Cast at the Center of the Storm

Arthur Hamilton Gordon, lieutenant-governor, acted not as a ceremonial figure but as a constitutional actor willing to use the full weight of his office. His DCB biography describes how he forced Smith to confront union questions, then precipitated a ministry crisis when Smith refused to cooperate over Gordon’s reply to the Legislative Council.

Albert James Smith, the anti-Confederate premier, was a sharp lawyer with what his biographer calls a “rapier tongue,” leading a coalition that could win an election but struggled to govern under imperial and constitutional stress.

Peter Mitchell, “Bismarck Mitchell,” the hard-driving Confederation organizer, became premier when Gordon engineered the transition and Tilley could not immediately lead from the assembly. The DCB describes Mitchell leading “the fight for confederation during the 1866 election,” which ended in a major victory.

Samuel Leonard Tilley, the Confederation face of New Brunswick, remained central even when not technically premier in the election moment—symbol, strategist, and ultimately the colony’s most famous Confederation father.

Timothy Warren Anglin, anti-Confederate champion and lightning rod. His biography shows both his substantive arguments and the way Confederates turned him into the embodiment of alleged disloyalty.

Bishop James Rogers of Chatham, whose intervention demonstrates how, in 1866, sermons, letters, and political legitimacy could blur at the edge—religion as moral authority entering the electoral arena.

Strategy and Topics: How Each Side Fought

The Confederates fought a two-front campaign.

First, they fought on fear and protection: not panic for its own sake, but fear disciplined into a policy claim—union means security; disunion means exposure. Second, they fought on legitimacy: they presented Confederation as the sober, loyal path aligned with Britain’s strategic needs and the colony’s survival. Buckner captures the collapse of the anti-Confederate line in a single, brutal phrase: the “pro-American and isolationist policies” at the center of the previous election “lay in shatters.” In other words, the world had changed, and so did what sounded plausible on a hustings platform.

The anti-Confederates fought on constitutional principle and local interest: they warned against governors and councils driving policy over the people’s heads; they warned that the Quebec terms were unfair; they warned that New Brunswick would become a province of second rank inside a federation dominated by Canadian population and Canadian capital. Their best weapon was the charge that the process itself was being manipulated—an argument that grew sharper when Gordon forced the ministry crisis.

The Process and Events: The Election as a Sequence of Turning Gears

Here the 1866 story becomes a true political drama—because it is not only an election, but an election caused by a constitutional rupture.

Gordon’s biography lays it out: the anti-union government weakened; a by-election loss in York signaled shifting ground; Gordon pushed Smith toward a union resolution; the Legislative Council—more favorable to union—issued an address strongly supporting the Quebec plan; and when Smith refused to cooperate over Gordon’s intended reply, Gordon delivered it anyway, and the ministry fell. This was the turning point in the machinery: a governor using reserve power pressure and political timing to crack a ministry that had electoral legitimacy but lacked cohesion and momentum.

Then came dissolution and election. Buckner notes Gordon dissolved the assembly and called the vote; controversy over Gordon’s conduct became an issue, but did not decide the outcome. The deciding force was that the election was now held after the anti-Confederates’ previous themes had been discredited by events—especially the security crisis atmosphere and the loyalty campaign.

The Ebb and Flow: A Close-Range Description of the Election’s Motion

Think of the campaign as a tide moving through the colony.

Phase One: The constitutional quarrel becomes public spectacle.

In the wake of the ministry crisis, New Brunswick politics ceased to look like ordinary party rivalry and began to resemble a trial of the colony’s constitutional future. Gordon’s opponents tried to make his actions “unconstitutional” and paint him as a governor overriding responsible government. Gordon’s supporters replied that the colony’s safety and imperial destiny required firmness. The argument was not abstract; it was about who truly represented the people: a ministry with a prior electoral mandate, or a new alignment that claimed to represent the colony’s survival.

Phase Two: Loyalty becomes a hammer.

Anglin’s biography shows how Confederates turned “loyalty” into a method—an instrument to isolate anti-Confederates by associating them with Fenianism and annexation. The technique was political jiu-jitsu: instead of debating tariffs and representation, debate who can be trusted when danger comes.

Phase Three: Religion and identity enter as sparks.

The Anglin–Rogers controversy reveals how quickly the campaign could turn combustible. Rogers complained that Anglin was being deployed “because he was a Catholic, to excite the Catholic and Irish sympathy against the Governor… and against Confederation,” and he claimed it was “admitted by all” that Anglin’s Miramichi visit backfired. Anglin, in turn, accused Rogers of aiding those who would “force our country into Confederation.” This was not merely a clerical spat—it was the sound of blocs being courted, accused, and re-sorted.

Phase Four: The security crisis tightens the vote.

Gordon’s biography explicitly ties the campaign climate to the Fenian threat: the invasion scare “alerted the electorate to the greater security that federation would provide.” Even those skeptical of the Quebec terms could now be made to imagine militia musters, border alarms, and a colony standing alone. It is the classic moment when external pressure compresses internal debate.

Phase Five: The polling and the swing.

By May–June 1866 the result was decisive: pro-Confederates won 33 of 41 seats, leaving 8 to the anti-Confederate “constitutionalists.” Buckner adds texture: outside Acadian strongholds, the election was “largely a disaster” for the anti-Confederates. Gordon’s biography adds the scale: unionists polled “about 60 per cent of the vote.”

A Brief “Real-Time” Snapshot: What It Felt Like

In real time, the election did not feel like a clean philosophical choice. It felt like a narrowing corridor. Men who had defeated Confederation in 1865 now faced a new map of fear: British officers and militia preparedness; rumors and reports from the American border; the insinuation that opposition equaled disloyalty; and the sense that London and the Canadians had decided what direction history ought to take. On the other side, Confederates felt the urgency of a last chance. If New Brunswick stayed out, the grand project might remain a Canada-only bargain—marooned from the sea, politically incomplete, strategically awkward.

Results: What the Election Immediately Produced

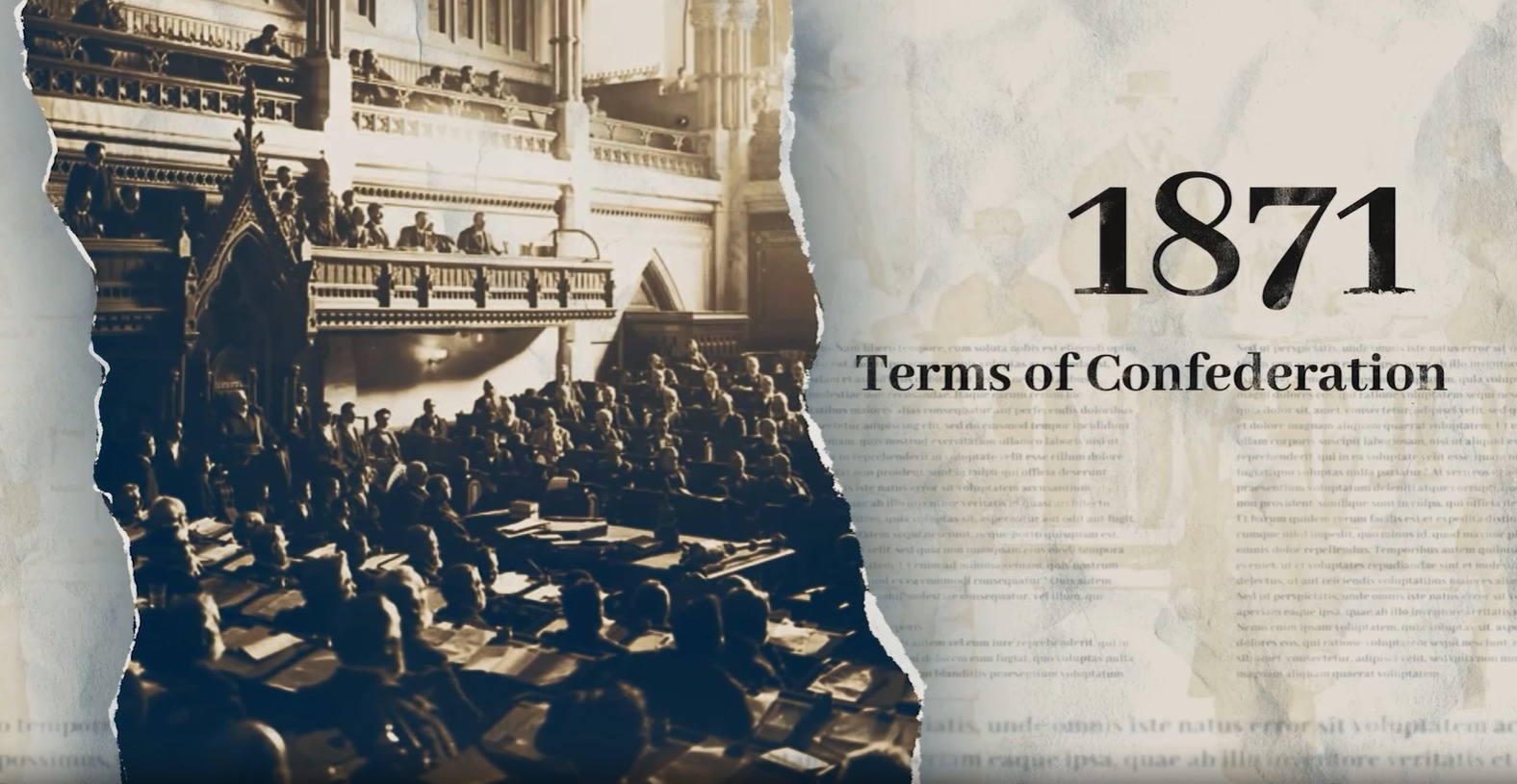

Once the Confederates won, the path cleared quickly. Buckner notes that Albert James Smith brought forward motions such as a referendum call and changes to Senate representation, but they were “easily defeated” by the new government, which passed the necessary resolutions to send delegates to London. In other words, after the election, the machinery no longer hesitated. The colony moved from debating Confederation to implementing it.

Why It Was So Important: The Broader Effects on Canada’s History

1) It made Confederation physically possible.

Without New Brunswick, the founding federation would likely have been smaller, less coherent, and strategically compromised. The intercolonial railway—so central to security and economic integration—was bound up with New Brunswick’s participation, and Gordon himself viewed the railway as “crucial” to the larger goal.

2) It showed how external threat can accelerate constitutional change.

Here the historians’ voices become essential. Military historian C. P. Stacey argued that “No mere constitutional proposal” could have awakened the feeling stirred by Fenian threats. That insight explains New Brunswick’s pivot: policy arguments alone did not flip the colony; crisis atmosphere did.

3) It normalized the idea that Confederation would be settled by elections, not plebiscites.

Anti-Confederates demanded referendums; Confederates accepted elections as the proving ground. After May–June 1866, that question was answered in practice: electoral victory provided the mandate, and London would finish the law.

4) It hardened political tactics that would echo after 1867.

The “loyalty” campaign—effective, sometimes unfair—demonstrated how identity and security could be weaponized in British North American politics. Anglin’s story shows both the potency and the damage of such framing, especially when Irish Catholic communities were cast under suspicion for political advantage.

5) It re-sorted minority politics in the Maritimes.

Buckner’s account highlights the shifting Irish Catholic vote and the relative steadiness of Acadian anti-Confederate support in certain counties. The election became, among other things, a demonstration that minority communities were not monoliths—and that clergy and community leaders could influence outcomes dramatically.

Conclusion: The Election as Confederation’s Atlantic Key

In the end, the New Brunswick election of 1866 mattered because it transformed Confederation from a contested blueprint into a forward-moving train—one that could now reach the sea. It was important not only for its seat count, but for what it revealed about the Confederation era: that constitutions are not merely written; they are won, under pressure, through coalitions that fracture and reform, through campaigns where fear and hope mingle in the same speech, and through turning points where a colony chooses whether to remain alone—or to gamble on becoming part of something larger.

Short Historian Quotations Used (as cited above)

- C. P. Stacey: “No mere constitutional proposal” could have awakened the same feeling as Fenian threats.

- Timothy W. Anglin (via DCB biography): opposition framed as “a conspiracy to defraud and cheat the people.”

- Anglin biography (DCB): “comic-opera Fenian raid” aided the loyalty strategy.

- Buckner: anti-Confederate “pro-American and isolationist policies…lay in shatters.”

References and Further Reading

Primary / near-primary (debates & documents)

- New Brunswick House of Assembly debates (June 1866), Confederation Debates Project (University of Victoria).

Scholarly biographies (academic reference works)

- J. K. Chapman, “GORDON, ARTHUR HAMILTON, 1st Baron STANMORE,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- C. M. Wallace, “SMITH, Sir ALBERT JAMES,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- (W. A. Spray), “MITCHELL, PETER,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- Biography of Timothy Warren Anglin, Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Peer-reviewed scholarship

Phillip Buckner, chapter on the Maritimes and Confederation debate (University of Calgary Press, open access).

William M. Baker, “The 1866 Election in New Brunswick: The Anglin–Rogers Controversy,” Acadiensis (PDF).

Election Details

1866 New Brunswick general election

Timing

- Held: May–June 1866

- Polling took place over several weeks (as was customary in colonial elections), rather than on a single uniform voting day.

- The election was called after Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon dissolved the legislature following the fall of the anti-Confederate government.

Seat Totals (Legislative Assembly – 41 seats)

- Pro-Confederates: 33 seats

- Anti-Confederates (Constitutionalists): 8 seats

This represented a decisive reversal from the 1865 election, which had rejected Confederation. The 1866 result gave a clear mandate to proceed with union negotiations and send delegates to London, paving the way for New Brunswick to become one of the founding provinces of Canada on July 1, 1867.

Election Deep Dive

Saint John and the North Shore, 1866: Ports, Parishes, and the Making of a Dominion

In the late spring of 1866, New Brunswick did not so much cast ballots as reveal its soul. The colony was small enough to fit within a rider’s hard week in the saddle, yet divided enough to feel like two countries arguing across a river. At one end stood Saint John—salt-stung, mast-crowded, impatient with hesitation. At the other lay the North Shore—Miramichi, Gloucester, Caraquet—where timber wealth rose and fell with the rivers, and politics flowed through parishes as much as through newspapers. Confederation, for these regions, meant different futures. The election of 1866 was the moment when those futures collided.

Saint John looked outward. Its harbor was a forest of spars, its merchants fluent in the language of bills of exchange and winter freight rates. The Reciprocity Treaty with the United States had expired; the American Civil War had demonstrated how swiftly markets could convulse. The port’s leading men calculated risk the way shipmasters calculated tonnage. To them, Confederation was not poetry but protection. The proposed Intercolonial Railway—binding the Atlantic to the interior of British North America—promised insulation against American tariffs and the fickleness of foreign policy. Without it, Saint John feared becoming a splendid backwater, eclipsed by Halifax or siphoned by Portland. With it, the port would anchor a new commercial geometry. The argument for union in Saint John was thus brisk and commercial: security of trade, certainty of rails, a broader market to replace the American one that had just slipped away.

North and east, along the Miramichi and into Gloucester County, the view was different. Timber men and smallholders did not see their ledgers mirrored in Saint John’s ambitions. Confederation, as sketched at Quebec, looked like an arrangement negotiated by distant men for distant ends. The North Shore had already flexed its muscle in 1865, helping defeat the first Confederation ministry. Suspicion of centralization, of Saint John dominance, of new taxes levied by strangers—these were not airy fears. They were grounded in experience. In Miramichi, the Irish-born editor and politician Timothy Warren Anglin gave that suspicion a cutting voice, denouncing the scheme as an elite contrivance that would cheat ordinary New Brunswickers of their right to decide. His rhetoric resonated where parish identity ran deep and political memory was long.

Yet politics in 1866 would not remain a ledger dispute between port and parish. It acquired the smell of powder. Fenian threats from across the American border—more alarming than effective—were enough to stir militia musters and sharpen imaginations. Military historian C. P. Stacey would later observe that no mere constitutional proposal could have awakened feeling like that aroused by the Fenian danger. In Saint John, this translated quickly into a language of loyalty. Confederation became not only prudent but patriotic. Opposition could be cast, subtly or bluntly, as softness toward republicanism or worse. The port’s Protestant majority heard in union the steady cadence of British security.

On the North Shore the effect was more complicated. Irish Catholic communities, courted by both sides, became the campaign’s hinge. The so-called Anglin–Rogers controversy—between Anglin and James Rogers—revealed how thoroughly politics had entered the pulpit and the pew. Rogers publicly endorsed Confederation, insisting his position aligned with leading ecclesiastics elsewhere; Anglin accused him of aiding those determined to force the colony into union. Sermons became campaign texts. Parish loyalties intersected with party loyalties. In Gloucester’s largely Acadian districts, anti-Confederate sentiment remained comparatively firm, wary of cultural marginalization in a wider federation. But elsewhere along the North Shore, Irish Catholic voters began to drift toward the Confederates, persuaded by appeals to loyalty, security, and the promise of inclusion rather than exclusion in a British North America knit together.

Running beneath these arguments was the iron line of the railway. The Intercolonial’s projected route was not abstract; it was destiny etched in survey stakes. Saint John saw in it commercial salvation. North Shore communities wondered whether the line would feed the port’s dominance or genuinely bind the colony’s disparate regions. Rail geography became political geography. Every mile of projected track seemed to add a pound to one side of the electoral scale.

The campaign’s ebb and flow reflected these pressures. In its early stages, anti-Confederate confidence in the North Shore appeared durable, buoyed by the triumph of 1865. Saint John’s enthusiasm for union, though fervent, could not alone carry the colony. Then came the ministry crisis precipitated by Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Hamilton Gordon and the collapse of the anti-Confederate government. Dissolution followed. The election became a referendum not merely on policy but on the colony’s direction under imperial scrutiny and continental uncertainty. As Fenian alarms echoed and loyalty rhetoric intensified, the tide began to turn. Irish Catholic districts that had once formed the backbone of resistance fractured. The anti-Confederate coalition—broad but brittle—lost cohesion. By the time ballots were counted, Confederates held 33 of 41 seats. The port had prevailed, but not alone; the North Shore had shifted enough to make resistance untenable.

In retrospect, the Saint John–North Shore divide illuminates the nature of Confederation in New Brunswick. It was not a seamless march of inevitability. It was a contest between economic visions: a port city wagering on continental integration, and rural river communities wary of surrendering autonomy to a larger design. It was also a struggle over identity—British loyalty against republican shadow, Protestant and Catholic leaders vying for moral authority, Acadian communities measuring the risks of absorption. Above all, it was a demonstration of how geography shapes politics. Harbors think differently than hinterlands; railheads reconfigure allegiances.

When New Brunswick entered Confederation in 1867, it did so because Saint John’s outward-looking commercial logic fused, under the pressure of security and persuasion, with a sufficiently altered North Shore electorate. In the creak of wharves and the hush of parish churches, the colony had chosen. The Dominion that emerged owed something to both: to the port’s ambition and to the timber country’s reluctant assent. Without that uneasy regional reconciliation in 1866, the Atlantic door to Confederation might have remained closed, and the map of Canada—so familiar now—would have been drawn differently.