By Greg Scott

History, as the old adage goes, is written by the victors. But now and then, the wind shifts, and a whisper from the past—half legend, half truth—becomes too loud to ignore. Such is the story of the Norse landings in North America, not in the Caribbean warmth that later drew Columbus, but in the fog-draped coasts of Newfoundland, where the cold is a living thing and the landscape broods with the weight of forgotten sagas. Before Columbus ever set eyes on a map, before Spain’s galleons carved empires across oceans, there were Vikings on the shores of Canada.

The Call of the West: Why the Vikings Came

The Norse, it must be said, were not explorers in the modern sense. They did not seek to “discover” — they sought to survive, to trade, to raid, and sometimes, to plant fragile settlements in lands crueler than their own. Driven by a mixture of ambition, curiosity, and the push-pull of climatic necessity, they set out into the Atlantic. By the late 10th century, Erik the Red had already carved out a home in Greenland. But Greenland was not Vinland.

Vinland—the land of wild grapes and fertile pastures—appears in the Vinland Sagas, two Icelandic texts that carry the faint scent of truth beneath their heroic embellishments. One, the Saga of the Greenlanders, tells of Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red, blown off course and landing in a place with dew “so sweet it tasted like honey.” The other, The Saga of Erik the Red, describes three Norse expeditions to this unknown coast, brimming with resources and danger alike.

The sagas, like much Norse storytelling, walk the line between myth and memory. But they are precise in one regard: Vinland lay to the west, beyond Greenland, where the sun shone longer and the winters were less cruel. According to historian Kirsten Seaver, “Vinland was not a place of fantasy but a remembered land… its contours recorded in collective memory long before archaeology confirmed it.”

The Landfall: L’Anse aux Meadows and the Edge of the World

In 1960, the saga found a shoreline.

Helge Ingstad, a Norwegian explorer, and his wife Anne Stine Ingstad, an archaeologist, uncovered the remains of a Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northern tip of Newfoundland. It was, at last, the tangible proof that the sagas had preserved more than folklore. Radiocarbon dating placed the site at around AD 1000. The structures bore the unmistakable stamp of Norse architecture—turf walls, iron nails, and the blackened remnants of iron smelting hearths, something unknown among the Indigenous cultures of the region at the time.

Here, on the edge of the known world, the Norse built halls, worked metal, repaired ships, and perhaps, looked westward once more. “It was not a colony in the grand sense,” writes archaeologist Birgitta Wallace, “but a base camp—a seasonal outpost, likely used for exploration, timber-gathering, and repair.”

Why Here? Why Then?

Newfoundland was no random choice. The sagas describe a coastline where rivers teemed with salmon and pastures invited grazing. The Norse needed timber, which was scarce in Greenland, and they needed a foothold closer to trade routes. Wallace notes that L’Anse aux Meadows was “strategically located for explorations farther south and was likely one of several seasonal sites.”

The term Vinland itself likely refers not to wild grapes—as originally romanticized—but to meadows or “wine-berries,” perhaps cranberries or cloudberries. Historian Gwyn Jones emphasizes that the Norse were practical: “They named places for what they found there. Iceland had ice. Greenland, despite its name, was not green. Vinland had value.”

Encounters at the Edge: Norse and Indigenous Peoples

There is no definitive record of the names or faces of those whom the Norse encountered in Vinland. But encounter them they did. The sagas speak of the Skrælingar, a term for Indigenous peoples—likely ancestors of the Beothuk or Mi’kmaq in Newfoundland. The narratives alternate between trade and hostility. In one vivid episode, a Norseman is struck dead by an arrow, leading to a chaotic retreat. The Norse were warriors, but they were not invincible. And unlike the later European empires, they were few.

Archaeological evidence of prolonged interaction is limited, though some scholars, such as William Fitzhugh, believe contact was “likely sporadic, fleeting, and not altogether peaceful.” Others speculate that the Norse may have carried diseases to which Indigenous peoples had no immunity—setting the stage for tragedy centuries before smallpox blankets were ever conceived.

The Retreat from Vinland

Despite the promise of Vinland, the Norse did not stay. The reasons, like so many endings in history, are manifold. Isolation, the difficulty of resupply, internal strife, and Indigenous resistance likely played their parts. “It was not a defeat,” writes Fitzhugh in The North Atlantic Saga. “It was a recalibration. The Norse understood their limits.”

There was no resounding battle, no last stand. The halls were abandoned. The fires died. The wind buried what the sagas preserved. And so, the Norse disappeared from North America, leaving behind neither empire nor colony, but ruins and a riddle.

What Was Left Behind: Archaeology and Memory

Today, L’Anse aux Meadows is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Visitors can walk among the reconstructed halls, feel the bite of the wind, and imagine longships bobbing in the bay. The site remains the only confirmed Norse settlement in North America, but other tantalizing clues continue to stir debate. Norse-style artifacts found along the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in Labrador hint at a broader footprint, but nothing has matched the clarity of L’Anse aux Meadows.

“The question is not whether the Norse reached the New World,” said Annette Kolodny in her landmark study In Search of First Contact, “but how long they stayed, how far they traveled, and why we tried so long to forget them.”

Historiography: From Hoax to Heritage

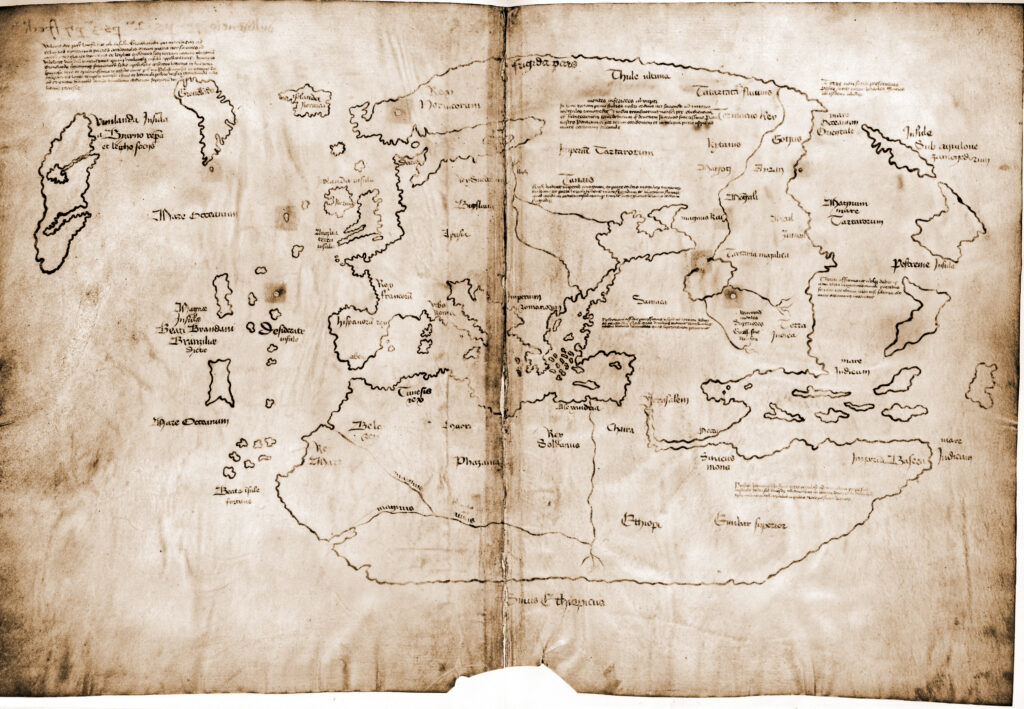

For centuries, the notion of pre-Columbian Norse contact was dismissed as legend. The Vinland Map, purportedly showing Norse exploration before Columbus, was exposed as a forgery, further muddying the waters. But archaeological rigor has slowly replaced romanticism.

Modern scholars such as Fitzhugh, Wallace, and Kolodny have reframed the conversation. Rather than seeing the Norse as conquerors, they see them as part of a much older narrative of trans-Atlantic movement. As Heather Pringle wrote in National Geographic, “The Vikings were not history’s footnote in the New World. They were its prologue.”

The broader historiography has shifted from the triumphalism of “first discovery” to a more nuanced examination of contact zones—where cultures met, clashed, and changed. “To understand the Vikings in America,” Kolodny argues, “we must unlearn the myths we’ve inherited and listen, instead, to the layered voices of saga, soil, and shoreline.”

Conclusion: A Legacy of Possibility

The Norse did not plant a flag, nor claim dominion over continents. But they were here—more than four centuries before Columbus. They came not for conquest but for sustenance, not to evangelize but to explore. And in doing so, they became part of a longer, more complicated story about who first touched these shores.

History, often forgets those who arrive too early. The Norse came not to write history but to test its margins. And though they vanished from the coast of Newfoundland, they left behind a haunting lesson: that even the most ephemeral presences can echo through a thousand years.

Select References:

- Fitzhugh, William W. Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga. Smithsonian Institution, 2000.

- Wallace, Birgitta. “L’Anse aux Meadows and Vinland: An Abandoned Experiment.” Archaeology, 2003.

- Kolodny, Annette. In Search of First Contact: The Vikings of Vinland and the Peoples of the Dawnland. Duke University Press, 2012.

- Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Seaver, Kirsten A. Maps, Myths, and Men: The Story of the Vinland Map. Stanford University Press, 2004.

- Haughawout, S. N. “Viking and Native North American Interactions.” Utah State University Honors Theses, 2024.