By Greg Scott

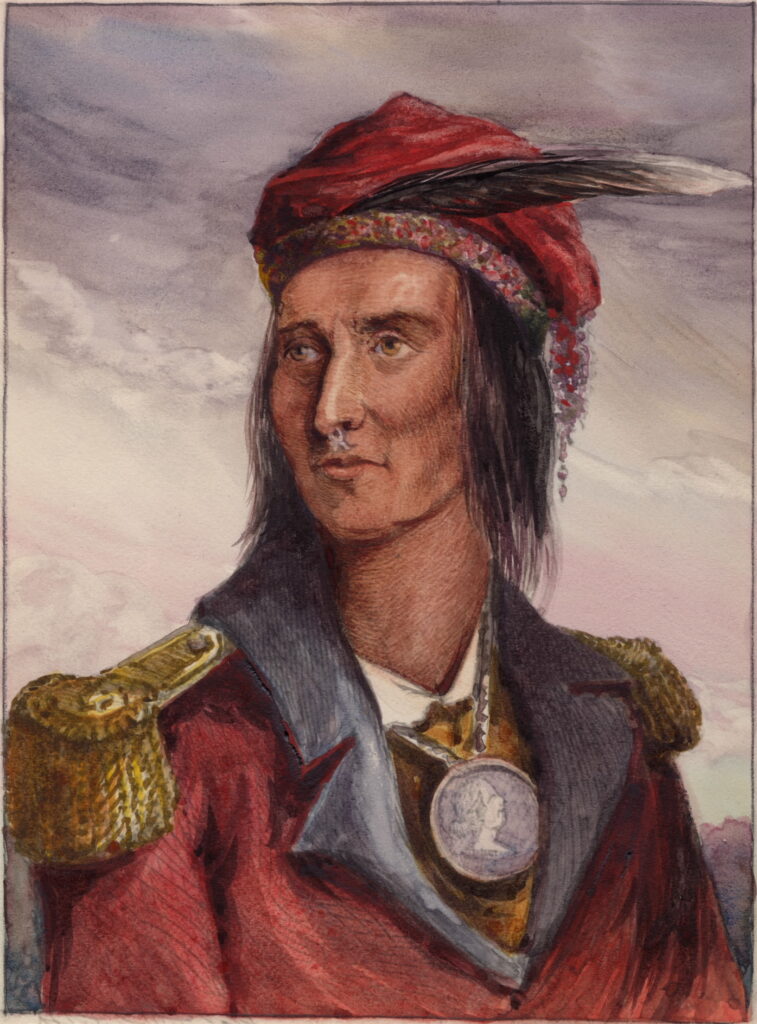

In the damp, dark woods of the Old Northwest—those deep woods that once breathed Shawnee prayers and the sounds of snapping muskets—rose a man unlike any other. He was called Tecumseh, meaning “Shooting Star,” and like a celestial body, he flashed brightly, burned brilliantly, and was gone too soon. His mission? Nothing less than a resurrection—a coalition of native nations that would not kneel, that would not cede, that would not die quietly.

To tell his story is to tell one of the last great acts of defiance against manifest destiny. It is also to recognize the pivotal hand he played in shaping what would become Canada.

A Childhood in Chaos

Tecumseh was born around 1768 near Chillicothe, in present-day Ohio. He came into the world just as the French and Indian War had ended, and just as a new wave of white settlers began sweeping across the Ohio Valley like a flood. His father was killed by colonists in the 1774 Battle of Point Pleasant, his mother disappeared from records soon after, and his twin brother died in infancy. His remaining family would be as marked by spiritualism as he was by martial destiny.

What forged him wasn’t just trauma—it was patterned betrayal. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784) and other U.S. treaties signed without Indigenous consent disgusted him. While many tribes tried appeasement, Tecumseh believed accommodation was suicide. His early years saw combat with U.S. troops and settlers, and he earned a name for brilliance in skirmishes like the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794). Unlike many leaders, Tecumseh refused to sign the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which ceded much of Ohio to the United States. His silence was its own declaration of war.

The Prophet Rises: Tenskwatawa and the Religious Revolution

If Tecumseh was the sword, Tenskwatawa, his younger brother, was the voice. Originally known as Lalawethika (“The Rattle”), Tenskwatawa was a failed drunk and a mockery in his own village—until 1805. After falling into a trance-like state, he awoke claiming visions from the “Master of Life.” He demanded Native peoples reject alcohol, European dress, Christianity, and American ways. The transformation stunned even his enemies. This was the beginning of a religious revival movement. Historian Carl Benn (2015) observed: “No movement like this had emerged since the days of Pontiac.” Tenskwatawa renamed himself The Prophet, and he became the spiritual spark of a broader pan-tribal awakening.

This was the beginning of a religious revival movement. Historian Carl Benn (2015) observed: “No movement like this had emerged since the days of Pontiac.” Tenskwatawa renamed himself The Prophet, and he became the spiritual spark of a broader pan-tribal awakening.

Building a Native Nation: The Pan-Indigenous Confederacy

To the American frontier generals who feared coordinated Native resistance more than they feared red-coated British troops, the vision of Tecumseh was their greatest nightmare: unity. Not merely a military alliance, but a continent-spanning coalition of Indigenous nations governed by shared sovereignty and guided by both political clarity and spiritual revival. At the heart of this movement stood Tecumseh, the warrior-statesman, and his brother Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee Prophet.

Prophetstown, founded by the brothers around 1808 near the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers in what is now Indiana, became the symbolic and strategic center of this Indigenous awakening. More than a village, it grew into the largest Native settlement in North America by 1811, housing between 5,000 and 6,000 people from over a dozen tribes. Shawnee, Miami, Kickapoo, Potawatomi, Sauk, Fox, Winnebago, Ojibwe, Ottawa, Delaware, and others gathered there—not just to take up arms, but to hear the Prophet’s teachings and join the cause. Prophetstown was a rare phenomenon: a pan-tribal capital city, offering not just safety but vision.

The spiritual core of the movement came from Tenskwatawa, who, after a personal transformation in 1805, declared himself chosen by the “Master of Life.” He preached a rejection of white customs, especially alcohol, Christianity, and European technology, urging a return to ancestral values. His sermons drew many followers, especially younger warriors frustrated by years of land loss and political compromise. But if the Prophet was the soul, Tecumseh was the architect. He envisioned something even more ambitious—a confederation of Indigenous nations united by the belief that no single tribe could sell land, because all land was held in common by all Native peoples.

Beginning in 1810, Tecumseh embarked on a monumental diplomatic campaign that would span thousands of miles. His goal was to bring the southern and western nations into the alliance. Traveling on foot and horseback, Tecumseh addressed the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and even the distant Osage. His speeches were urgent, eloquent, and impassioned. “The white men are not friends,” he warned. “They take and never give. They cheat and lie and steal. If we do not resist together, we will be divided and destroyed one by one.” More than just a call to arms, Tecumseh’s argument was revolutionary: no tribe had the right to sell land because it belonged to all Native peoples. This notion directly challenged the U.S. treaty system, which had long relied on negotiating with individual tribes to divide resistance and acquire land piecemeal.

The responses he received were mixed. The Cherokee, pursuing a strategy of diplomacy and assimilation, refused to join the movement. The Chickasaw and Choctaw were similarly cautious, preferring peace. The Creek nation was split—while many elders remained neutral, younger warriors known as the Red Sticks were electrified by Tecumseh’s words. His presence is widely credited with fueling the growing radicalization that would erupt into the Creek Civil War in 1813. Frustrated by rejection, Tecumseh reportedly warned his southern audience that if they failed to join the confederacy, they would be counted as enemies. At one council, he is said to have declared, “When I return north, I will stamp my foot and the earth will shake.” Days later, the 1811 New Madrid Earthquake—one of the most powerful in North American history—rattled the Mississippi Valley. Many who had doubted him began to believe he possessed supernatural power.

Tecumseh’s vision was vast and clear. He aimed to establish a permanent Indigenous homeland stretching across the Old Northwest—protected by Native arms and British alliance but governed by pan-tribal unity. Historian Jon Sugden has described him as a “federalist nationalist,” one who sought unity not through cultural assimilation, but through shared sovereignty. Each tribe would retain its identity and customs, but all would act as one in matters of war, diplomacy, and land defense. Such a confederacy would stand as a third power on the continent—alongside the United States and British Canada—capable of checking American expansion.

Yet unity required time, and time was not on Tecumseh’s side. In November 1811, while he was still in the South continuing his campaign, U.S. forces under William Henry Harrison launched a surprise assault on Prophetstown. In the ensuing Battle of Tippecanoe, the Prophet’s forces were defeated, and the village was burned. Though the spiritual movement was wounded, Tecumseh returned undeterred, prepared to lead the resistance into the next phase: war.

The Pan-Indigenous Confederacy Tecumseh built would never reach the scale he imagined, but it remains the most ambitious attempt to forge lasting Indigenous unity on the continent. It was not merely a military alliance; it was a revolutionary model of intertribal governance. And it left a legacy that would echo through later generations of Native resistance.

Tippecanoe and the Collapse

In November 1811, while Tecumseh was away in the South, U.S. forces under Governor William Henry Harrison launched a preemptive strike against Prophetstown. The Battle of Tippecanoe saw the Prophet’s forces routed, despite his mystical promises of victory.

Though technically a draw, the defeat crushed the movement’s aura of invincibility. “The spell was broken,” wrote historian R.S. Allen (1988). Tenskwatawa’s credibility suffered. Tecumseh, returning weeks later, was furious. Yet his military command remained unshaken.

What was lost in Tippecanoe was a window—the opportunity to confront U.S. power before it coalesced. But fate intervened again: war came in 1812.

The British Alliance and War of 1812

When war officially broke out between the United States and Britain in June of 1812, Tecumseh saw not disaster, but opportunity. For more than a decade, he had worked to build a pan-Indigenous confederacy capable of resisting American expansion. Now, with Britain once again at war with the United States, he recognized the moment to shift his movement from regional defense to continental strategy. Unlike past, often one-sided alliances with European powers, this one—if he could shape it—would be active, cooperative, and mutually beneficial. And, crucially, it would have to be made on equal footing.

In British Major-General Isaac Brock, Tecumseh found not just a military ally but a rare kindred spirit. Brock was a career officer—disciplined, daring, and known for his disdain of indecision. He respected Tecumseh’s command ability, his intelligence, and most unusually for a British commander of the era, his nation’s sovereignty. Their first meetings were marked by mutual admiration. Brock later remarked that “Tecumseh is the Wellington of the West,” comparing him to Britain’s most celebrated general, the Duke of Wellington. Tecumseh, in return, praised Brock as the first white man he had met who “did not talk to me like a child.” Their alliance was not born of convenience—it was built on respect and shared necessity.

With Brock’s support and the growing threat of American invasion into Upper Canada, Tecumseh pledged to take up arms not only in defense of Indigenous homelands but also to protect British colonial territory. This was not submission—it was strategic alignment. Tecumseh believed that the British might, if properly persuaded, help establish a permanent Indigenous territory in the Great Lakes region as a buffer between Canada and the United States. For a moment, history seemed to be turning his way.

The alliance’s first major test came in August 1812, when American General William Hull, commander at Fort Detroit, threatened to invade British Canada. Brock moved swiftly to counter the invasion, and Tecumseh brought his warriors—some 600 in number—to assist. Despite being outnumbered by Hull’s 2,000 men, the British-Indigenous force, totaling only around 1,300, executed a bold psychological strategy. Tecumseh’s warriors engaged in war chants, painted their faces for battle, and moved repeatedly through gaps in the forest to create the illusion of a much larger force. Hull, reportedly terrified by the prospect of a brutal massacre at the hands of Native warriors, surrendered without a single shot being fired.

The capture of Fort Detroit was more than a tactical victory. It sent shockwaves across the continent. The British celebrated; American morale plummeted. For Tecumseh, it was vindication. He had proven that Native warriors could not only match but outmaneuver professional armies. And it solidified his position—not as a subordinate, but as a field commander and political leader to be reckoned with.

The months that followed saw Tecumseh continue to fight with disciplined aggression. In early 1813, his warriors blocked American advances at the Battle of Frenchtown near the River Raisin, delivering a devastating blow to U.S. forces attempting to retake Michigan Territory. Though the conflict was marked by brutality—many American prisoners were later killed by Native forces after the battle—it demonstrated Tecumseh’s unrelenting commitment to defending the lands of the confederacy. He would go on to hold the Thames River line, coordinating skirmishes and ambushes that forced the U.S. military to commit thousands of troops just to defend their own frontier.

But even as Tecumseh succeeded on the battlefield, his political dream—the creation of a Native homeland under British protection—began to fray. While Brock had supported Tecumseh’s aspirations and understood the strategic value of such a buffer state, Brock’s sudden death in October 1812 at the Battle of Queenston Heights removed the one British commander who treated Tecumseh as an equal. In his place came men of lesser vision: cautious, bureaucratic, and ambivalent toward Native concerns.

General Henry Procter, who replaced Brock in the west, lacked both Brock’s resolve and his respect for Indigenous allies. His failures to consult Tecumseh, his reluctance to provide adequate supplies, and his repeated retreats weakened Indigenous morale. Tecumseh, increasingly frustrated, accused Procter of cowardice. “You are like a fat dog who carries his tail between his legs,” he said, after Procter proposed abandoning their position at Amherstburg. The alliance that had once glimmered with promise now grew strained and fragile.

British promises regarding Indigenous land claims were consistently vague, and in many cases, simply noncommittal. Tecumseh had hoped to win formal recognition of a Native buffer state in the Old Northwest, but British officials, focused on defending Canada rather than reshaping the continent, never offered more than general support. As historian Carl Benn noted, “To the British, Indigenous allies were instruments of war, not partners in peace negotiations.” And to Tecumseh, such duplicity was a betrayal of not just political trust, but of shared honor.

Yet even amid this disillusionment, Tecumseh fought on, leading from the front and rallying his warriors for what he knew would be a final confrontation. The death of Brock had not yet killed the dream—but it had taken away its strongest hope for realization.

Death at the Thames

By the autumn of 1813, the fragile hope that had once lit the alliance between Tecumseh and the British Crown had begun to collapse under the weight of shifting military realities. The Battle of Lake Erie in September of that year, led by the bold American Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, was a turning point. The U.S. Navy’s decisive victory gave the Americans control of the Great Lakes, severing critical British supply lines into Upper Canada. Without control of the water, British forces under Major General Henry Procter found themselves isolated, under-equipped, and increasingly desperate.

Rather than hold their ground, British leadership chose to retreat inland, abandoning Fort Detroit and falling back along the Thames River toward Moraviantown, deep in Upper Canada. For Tecumseh, who had dedicated years to forging a pan-Indigenous confederacy and defending these lands, the retreat was not just a tactical withdrawal—it was a spiritual and political betrayal. Procter, already seen by many Indigenous warriors as indecisive and weak, had shown little concern for Tecumseh’s vision or the fate of his people. When the general once again proposed pulling back, Tecumseh—livid and disgusted—confronted him with one of the most stinging rebukes of the war: “You are like a fat dog running away with its tail between its legs.”

This wasn’t mere rhetoric. Tecumseh knew the consequences of retreat. The territory they were abandoning had been purchased with Native blood, and the alliance with Britain had been based on the shared objective of defending that land. If the British would not stand and fight, Tecumseh would. He resolved to make a last stand, regardless of the odds.

On October 5, 1813, at the Battle of the Thames, Tecumseh and a force of around 500 warriors—mainly Shawnee, with support from the Wyandot, Delaware, and some Potawatomi—prepared to face an American army of over 3,000 men, under the command of General William Henry Harrison. The British, led reluctantly by Procter, did little to support their Indigenous allies. Many British troops fled early in the battle, leaving Tecumseh’s forces to fight alone. Isolated and outnumbered, the Native warriors fought fiercely along the wooded banks of the Thames River.

Tecumseh himself, as always, fought in the thick of the action, refusing to wear British colors or retreat. He understood fully that this was the final chapter, not just of the campaign, but likely of the entire Indigenous resistance movement in the eastern United States. His presence, it is said, was magnetic—even in the face of certain death, he inspired warriors to stand their ground.

In the confusion and violence of battle, Tecumseh was killed. The precise moment of his death was never recorded. Some accounts claimed that Colonel Richard M. Johnson, a Kentucky cavalry officer, delivered the fatal shot, though this has never been confirmed. What is certain is that when the gunfire ceased and the smoke cleared, the great Shawnee leader lay dead—or was gone entirely. His body was never definitively found, fueling both legend and sorrow. Some claimed his remains were scalped and desecrated by American soldiers. Others whispered that his warriors carried his body away in secret and buried him where no white man would ever find him, so that he would never be defiled, even in death.

With Tecumseh’s fall, so too collapsed the dream he had lived and fought for. The pan-Indigenous confederacy, once on the verge of being recognized as a geopolitical force, dissolved almost overnight. Without its charismatic and unifying leader, the alliance fractured. Native military resistance in the Old Northwest rapidly faded. The British, now even less inclined to advocate for Native territorial claims, made no further serious effort to protect Indigenous sovereignty in the region. In the subsequent peace negotiations at Ghent in 1814, not a single Native representative was invited. The nations Tecumseh had tried to unite were left to fend for themselves, many eventually relocated, removed, or assimilated under U.S. policies.

Historians have long marked Tecumseh’s death as a watershed – a definitive end not only to a military alliance but to an Indigenous vision of continental resistance east of the Mississippi. In the words of author John Sugden, “His death extinguished the last organized attempt by Native Americans to resist U.S. expansion through unity and force.” To many in Canada, Tecumseh remains a hero and symbol of courage, his stand at Moraviantown seen as part of the struggle to preserve Upper Canada. In the United States, his story is more complicated—admired for his nobility in war, yet largely forgotten in the national memory he fought against.

What remains today is a legend built on iron conviction, dignity in war, and a tragic refusal to accept the betrayal of a people. Tecumseh died with a rifle in his hands and a confederacy at his back—but the nation he dreamed of never rose.

Tecumseh’s Impact on Canada

Tecumseh’s war was, on the surface, a desperate and heroic attempt to preserve Indigenous sovereignty in the Great Lakes region. Yet, in a broader historical sense, his resistance inadvertently contributed to the survival—and eventual shaping—of Canada as a distinct political entity. Though his goal had never been to support British colonialism, Tecumseh’s military genius and strategic alliance with the Crown provided the buffer and breathing space that British North America desperately needed in the chaotic early years of the War of 1812.

His early victories at Fort Detroit and along the Thames frontier did more than repel American forces—they disrupted an entire U.S. war plan. The American invasion strategy hinged on a swift strike through the western Great Lakes into Upper Canada, with the ultimate goal of taking Montreal, cutting off British supply chains, and ending the war quickly. Tecumseh’s warriors, alongside British troops under General Isaac Brock, dismantled that ambition. The surrender of General William Hull at Fort Detroit in August 1812, achieved largely through Tecumseh’s psychological tactics and battlefield deception, was a humiliation for the United States and a major morale boost for the British. The delay this caused forced the Americans to reallocate troops, slow their advance, and reconsider their approach to the entire northern front.

As the war dragged into 1813, Tecumseh’s continued resistance at Fort Meigs, the River Raisin, and along the Thames River corridor served a greater strategic function: he bought time. Time for British reinforcements to arrive. Time for Canadian militias to organize. Time for local populations—loyalist farmers, fur traders, Métis communities—to consolidate their defensive identity. As historian James Laxer (2012) notes, “Tecumseh bought Canada time.” Without that buffer, it is entirely plausible that American forces would have pressed eastward, encircling the St. Lawrence corridor and isolating Montreal. Had that occurred, Upper Canada may not have survived the war intact.

More subtly, but perhaps more lastingly, Tecumseh’s alliance with the British helped catalyze the formation of a “Canadian” identity—not yet independent, but already distinct. According to historian S.M. Smith (2017), the shared struggle to repel American forces—alongside Indigenous allies like Tecumseh—produced a wartime consciousness among Upper Canadian settlers. This identity was defined not only by loyalty to the British Crown, but also by non-American-ness. These settlers weren’t merely Britons abroad; they were people who had fought to hold the land under their own feet, often side-by-side with Indigenous warriors. The common cause they shared with Tecumseh in the field—regardless of the politics at the negotiating table—gave shape to a nascent Canadian nationalism, one rooted in defense rather than conquest.

And yet, here lies the historical irony, one that runs deep. Tecumseh did not fight to protect settlers, nor to strengthen the British Empire. He fought to build a Native homeland—a sovereign Indigenous buffer state carved from the Old Northwest, stretching across modern-day Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and parts of Ontario. He envisioned a land where Indigenous governance, law, and culture could thrive independently, protected by alliance but not subordinate to any foreign king. In reality, that dream was never realized, and British support for it evaporated after Tecumseh’s death in 1813. No such Indigenous nation was included in the postwar settlement. No boundary was ever drawn for the people who bled most for the cause.

Still, the British benefited enormously from Tecumseh’s war. His confederacy provided a mobile, motivated, and deeply effective military force at a time when British troops were stretched thin across the globe. His alliance gave political legitimacy to British efforts in North America and countered American propaganda that painted the war as a liberation. And perhaps most fatefully, his sacrifices helped preserve British control of Upper Canada, allowing it to evolve over the next half-century from a military outpost into a semi-autonomous dominion, and eventually into the modern nation of Canada.

Thus, Tecumseh stands as one of history’s most paradoxical figures. In life, he opposed both settler expansion and colonial manipulation; in death, he became one of the unacknowledged founders of Canada, not by intention, but by consequence. The nation he dreamed of—a united Indigenous confederacy—never took form. But the nation he inadvertently helped save took root and eventually thrived. Canada, in part, was made in the shadow of Tecumseh’s final stand.

Quotes

- Tecumseh to Harrison (1810): “Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds, and the great sea, as well as the earth?”

→ A powerful indictment of colonial land ethics. - General Brock on Tecumseh: “A more gallant and sagacious warrior does not exist.”

→ Sign of mutual respect and alliance on equal footing. - Historian Carl Benn (2015): “Tecumseh represented the most serious threat to U.S. expansion in the interior since Pontiac.”

Further Reading

- Allen, R.S. (1988). His Majesty’s Indian Allies: Native Peoples, the British Crown and the War of 1812. The Michigan Historical Review. JSTOR

- Benn, C. (2015). Aboriginal Peoples and their Multiple Wars of 1812. Routledge Handbook of the War of 1812.

- Laxer, J. (2012). Tecumseh & Brock: The War of 1812. Between the Lines.

- Smith, S.M. (2017). The Canadian Bicentennial and the Problem of Tecumseh. ProQuest.

- Stanley, G.F.G. (1950). The Indians in the War of 1812. Canadian Historical Review.

- Sugden, J. (1986). Early pan-Indianism: Tecumseh’s tour of the Indian country, 1811–1812. American Indian Quarterly.

- Brownlie, R.J. (2012). The Co-optation of Tecumseh. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association.

- Robertson, J.T. (2012). John Strachan and the Indigenous Peoples. Ontario History.

- Conn, Z. (2022). The Ambassadors: Indigenous Democracy and American Monarchy after the War of 1812. Yale University.

- Graves, D.E. (2007). His Majesty’s Aboriginal Allies. In: Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian Military.