The birth of a city

By Greg Scott

Long before the clang of steel rails or the deceptive promise of surveyor flags fluttered in the prairie wind, the land that would become Brandon existed in a state of dignified antiquity. Here, on the wide shoulders of the northern plains, Cree, Ojibwe, and Sioux peoples lived lives bound not by borders but by the undulating rhythms of the earth. To them the Assiniboine River was not merely a watercourse but a venerable and constant companion—its bends, shallows, and meadows known with an intimacy Europeans could never truly understand. Their seasonal movements traced ancient knowledge: where the bison herds gathered in great thunderous multitudes; where trading parties could meet under the watchful eye of the sky; where medicines grew, hidden yet plentiful; and where winter could be endured with dignity. The valley’s significance was spiritual as well as practical, a place etched with stories that stretched far beyond memory.

When Europeans finally began to arrive in earnest during the nineteenth century, Indigenous communities faced an unfamiliar and increasingly coercive order. Fur traders brought both commerce and chaos. Government agents—often armed with policies shaped thousands of miles away—brought treaties that promised security while quietly extracting sovereignty. The people of the plains, already strained by disease and the collapse of bison herds, were confronted with the arrival of a new kind of empire: the empire of surveyors, speculators, and railway men. For Indigenous peoples, the railway was not a marvel of engineering but a harbinger of the industrial revolution. Land was sliced into parcels by men who believed in property lines with religious fervour. Treaties such as Treaty 2, signed decades before the CPR arrived, were interpreted by Ottawa allowed settlement, while Indigenous leaders protested that their understanding had been very different.

By the early 1880s, this uneasy landscape was pierced by the advance of the Canadian Pacific Railway, whose mission was nothing less than national consolidation. Surveyors—grim-faced men with canvas tents and iron instruments—walked the grasslands under the relentless prairie sun, searching for the path the line would take.

What they sought was efficiency: grades that would not cripple locomotives, ground firm enough for railbeds, and expanses wide enough to accommodate sidings and yards. But hovering behind every technical calculation was a political one. The CPR was not simply a railway; it was the Dominion’s most powerful corporate entity and an unspoken partner in the nation’s expansionist project.

At the confluence of ambition and geography lay the Grand Valley settlement, a hopeful but fragile cluster of tents and wooden shacks perched on the lower flats of the Assiniboine. Its residents watched the advancing survey crews with the rapt attention of men awaiting judgment. They had invested their savings, their pride, and their wildest hopes in the belief that the railway would pass directly through their settlement. Land that only months earlier had been nearly worthless was suddenly the subject of overheated conversation. Speculators swaggered, merchants boasted, and settlers waited for the steel to arrive like parishioners waiting for a miracle.

But the CPR, for all its transformative power, was not a charitable institution. Its decisions were guided by the hard calculus of terrain, profit, and strategic advantage. William Cornelius Van Horne, the company’s titanically driven general manager, believed with unfaltering certainty that a railway did not follow towns—towns followed the railway. When the surveyors deemed Grand Valley’s low-lying ground unsuitable, their verdict was swift and merciless. Two miles west, where the land rose and spread into a broad table above the river, the CPR staked out a new townsite. It was here that Brandon would be born—not out of the ambitions of settlers but from the deliberate, corporate will of a railway empire.

The consequences were immediate and spectacular. Grand Valley collapsed almost overnight, its residents displaced not by fire, flood, or famine but by a decision made in a railway office. Brandon, meanwhile, erupted into existence with a frenzy that would have made a gold-rush boomtown blush. Land prices soared into absurdity; lots that might have sold for $50 were suddenly worth ten or twenty times that amount.

The CPR, well-practiced in the art of making money from both steel and soil, ensured that it controlled the most valuable strips of land: the station grounds, yard limits, industrial parcels, and adjoining commercial districts. Property rights were dispensed by the company with the serene authority of a monarch distributing favour.

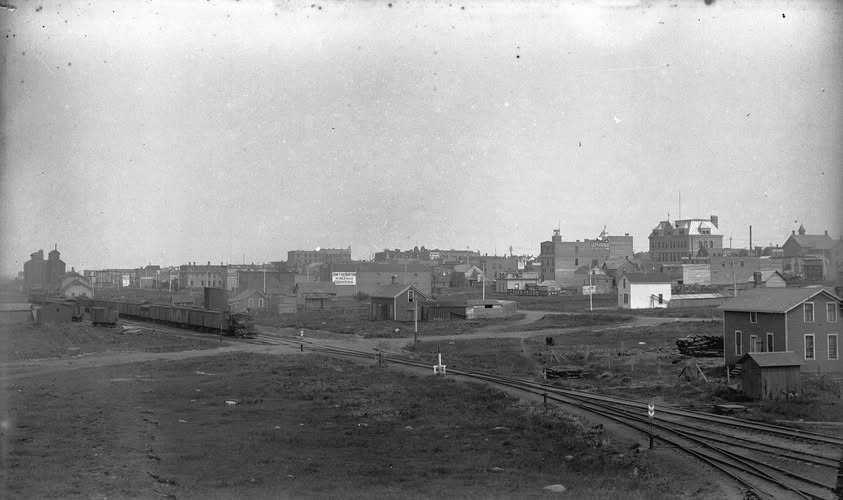

As the rails advanced and locomotives puffed their way into the new town, Brandon entered its first great transformation. The 1880s and 1890s were years of clamorous growth. Streets were graded, wooden sidewalks laid, and buildings erected at a staggering pace. Hotels, saloons, livery stables, and general stores crowded the central district. Immigrants arrived in droves: Scots with weathered faces and Presbyterian resolve, Ontarians eager for farmland, Ukrainians fleeing empire, and British labourers drawn by the promise of rail wages. Brandon became a hub of commerce, a depot for goods flowing into the West and wheat flowing out of it.

But beneath this flourishing enterprise lay a darker truth. The boom that brought prosperity to settlers had exacted a severe toll on Indigenous communities. Reserve lands were often established in areas that settlers considered marginal; hunting territories were destroyed by agricultural expansion; and the CPR’s right-of-way carved uninterrupted pathways across ancestral lands. The bison—their lifeblood—had vanished, victims of commercial slaughter and ecological collapse. Indigenous families moved, not with ancient rhythms of the plains, but under the pressure of change. The railway and the rising city were built atop this human cost, though few settlers paused to consider it.

Into the early twentieth century, Brandon settled into its identity as the Wheat City, the agricultural heart of southwestern Manitoba. Grain trains rumbled in and out of town like great iron beasts, pulling the region’s prosperity behind them. The Winnipeg Grain Exchange and CPR branch lines gave Brandon farmers access to global markets, and the town prospered accordingly. Brick buildings replaced wooden ones; electric lights flickered on; and the city’s civic institutions—schools, hospitals, churches—grew in stature.

The two world wars left their imprint as well. Brandon contributed soldiers to overseas service, and the community became a training centre during both conflicts. The postwar years brought suburban growth, industrial diversification, and civic pride. Yet even in these later decades, the shadow of the railway lingered. CPR still controlled strategic lands, and rail service remained a lifeline for local agriculture and commerce. When rail traffic surged, Brandon thrived; when it faltered, the city felt the tremor.

By the mid-20th century, Brandon had emerged as a balanced regional centre—its economy shaped not only by rail and agriculture but by education, with Brandon College evolving into a university, and by military infrastructure, particularly CFB Shilo nearby. The city weathered the storms that afflicted many prairie towns: droughts, economic downturns, and the gradual mechanization of farming that reduced rural populations. Yet Brandon endured with a kind of stoic resilience, its citizens accustomed to the cyclical nature of prairie life.

By 1990, Brandon had become a mature prairie city—diverse, industrious, and tempered by more than a century of boom and contraction. The railway remained, though no longer the imperial force it had been in Van Horne’s day. Indigenous communities, long marginalized, began asserting their rights with renewed vigor, and Brandon itself, increasingly aware of its layered history, began recognizing the deeper human story beneath its streets and grain elevators.

What emerged from this century-long passage was a city forged by ambition and tempered by hardship. Brandon’s story is one of steel and soil, of boom and restraint, of human hope set against the immense backdrop of the prairie. It is the story of a place where empire and aspiration collided, where Indigenous memory persists despite the scars of settlement, and where a railway—drawn almost carelessly across the grasslands—created a city that would shape the destiny of thousands. And as in all such stories, the land remembers, long after the rails have cooled and the surveyor’s flags have vanished into history.

References

Artibise, Alan F. J. Brandon: The Birth of a City. Brandon University Press, 1979.

Berton, Pierre. The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871–1881. McClelland & Stewart, 1970.

Carter, Sarah. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy. McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1990.

Daschuk, James. Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. University of Regina Press, 2013.

Miller, J. R. Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Norrie, Kenneth. “The CPR and the Development of Western Canada.” In The Railway and the Development of Western Canada, ed. Gerald Friesen, University of Manitoba Press, 1975.

Ray, Arthur J. I Have Lived Here Since the World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native Peoples. Lester Publishing, 1996.

Regehr, T. D. The Canadian Pacific Railway: A Century of Corporate Intelligence. University of Toronto Press, 2019.

Thompson, John. The History of Brandon University. Brandon University Publishing, 2006.

Further Reading

- Friesen, Gerald. The Canadian Prairie: A History. University of Toronto Press, 1987.

- Waiser, Bill. Saskatchewan: A New History (excellent for regional prairie context).

- Owram, Doug. Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West, 1856–1900.

- Wilson, J. Donald. Education and Society in Manitoba: Historical Essays.

- Manitoba Archives. Brandon Townsite Maps and CPR Land Records (primary sources).

- Brandon University’s S. J. McKee Archives (railway correspondence, early city records, Indigenous materials).